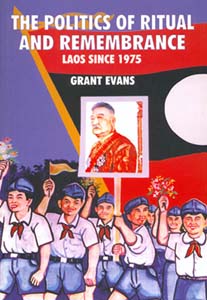

THE POLITICS OF RITUAL AND REMEMBRANCE LAOS SINCE 1975 by

Dr. Grant Evans Reader in Anthropology at the University of Hong Kong

(extract from page 89 to 113)

----- § ----- Recalling royalty A fact rarely noticed about King Sisavang Vong (1885-1959) of Laos is that at the time of his death on 29 October 1959 he was the longest reigning monarch in Asia, having ascended to the throne of Luang Prabang in April 1904. To be sure he only became the king of the whole of Laos in 1946 following a modus vivendi between the French and an increasingly assertive Lao nationalism. Nevertheless, compared to monarchs in surrounding countries this lifespan is, superficially at least, impressive. Given the often asserted central importance of the monarchy to Theravada Buddhist societies, the low profile of the Lao monarchy in its modern context.It has often been said that Lao monarchy in its modern context, respective monarchies only saw the modern world because of the protection given them by French colonialism. With an eye on the steady encroachments of both Vietnam and Siam on his territories the Cambodian king Norodom sought French protection in the mid-nineteenth century. Luang Prabang, still a vassal of Siam in the late nineteenth century, also sought French protection as a result of the depredations of marauding warlords from the borders of China. An 1893 treaty with Siam established French control over the land east of the Mekong. A protectorate was established over the kingdom of Luang Prabang (which included at that time the present provinces Luang Prabang, Oudomsay, much of Houaphan and later Sayaboury) where the king remained enthroned encompassed by a colonial system of indirect rule.(1) The annihilation of the aristocracy around Vientiane following Chao Anou's uprising against the Siamese in 1827-28, and the destruction of the Phuan kingdom in Xieng Khouang by Chinese warlords in the late nineteenth century, meant that the only other royal center in Laos was Champassak in the south, but this also had been enfeebled Siamese conquest in 1828, and so here the French ruled directly, simply allowing the royal family to maintain its aristocratic status. The king of Luang Prabang presided over his simple, traditional administrative structure, paralleled by a tiny number of French officials. He also continued to carry out the calendrical and ritual duties of a Buddhist monarch, as indeed did the prince of Bassac ( Champassak ). It may be asked, then, how does one legitimately claim to be a king or a prince of a ruling house under foreign colonial rule? The problem was particularly acute in the south where the prince of Champassak exercised no real power. Studies of ritual in the south by Archaimbault (1971) and a commentary on the latter by Keyes helps explain this. Rituals of purification of the realm previously carried out by mediums were taken over by the princes around 1900. "For the populace, the merit acquired by the princes by virtue of their position continued to generate (1)For a brief description of the initial French administrative structure in the north, see Raquez (1905: 1786-1791).

power; however, the power could be employed not in the secular realm but in the realm of the spirits of the locality. For the populace, the prince had become a priest, a substitute for the mediums of old" (Keyes 1972:613). One could say that in Luang Prabang throughout the French era and culminating in the formation of a constitutional monarchy, we see the progressive attenuation of royal power in the secular realm and its increasingly important ritual role in relation to the metaphysical realm. Direct questioning of French colonial power did not arise until the protective cloak of the French was swept aside by the Japanese during World War II. French administrative centralization had caused revolts in peripheral areas, as Geoffrey Gunn (1990) has documented, but these revolts were not specifically anti-colonial as Gunn and the current Lao government historiography would have it; rather, they were forms of resistance analogous to the revolts against modernizing state time (Chatthip 1984; Evans 1990b). Meanwhile, the king did not have to concern himself with defense of the realm, and this left him time to expend on ritual duties and on his role as defender of the faith. Indeed, the French assisted him financially in his duties and in fact the royal palace standing in Luang Prabang today was built for replace the one destroyed in 1887 by the Black Flag Chinese warlords and White Tai during the sack of Luang Prabang.

Even though the Japanese occupation shattered the aura of French colonialism and gave rise to a Lao independence movement, the Lao Issara, in which three members of Luang Prabang royalty figured prominently, the king remained loyal to the French. The reason for this appears to have been the king's fears that Laos could not protect itself from Chinese and Vietnamese encroachments. Hence he was briefly deposed by the Lao Issara after they had stepped into the power vacuum left by the Japanese in late 1945.(2) As the fortunes of the Lao Issara government faded as a result of fiscal problems and lack of international recognition, and in the face of French and pro-French forces, they offered to restore the king (Deuve 1992). Soon, however, the French re-established control and a little later, in 1947, Sisavang Vong became the first king constitutional monarch of the Royal Lao Government. But the conduct of the Lao monarchy in the 1950s and 1960s contrasted with Thailand where military dictatorships promoted a cult of the kin, and with the political activism of Cambodia's Norodom Sihanouk, who as king shrewdly led a "crusade for independence" and then stepped down as king in favour of his father in 1955 to engage in politics (Osborne 1994), Christine Gray (1991) has documented how the initial ritual competition between Field Marshal Phibunsongkhram and King Bhumibol Adulyadej gave way to co-operation under Phibun's successor Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat who "adopted the strategy of 'latching on' to or 'borrowing' the royal virtue. In 1959 he publicly observed that the king was upholding the ten virtues of the Dhammaraja, that he was farsighted and had a personality worthy of worship. For the first time since 1932, a Thai king was conveyed up the Chao Phraya River in a splendid royal barge procession to offer katthin robes at royal temples"(Gray 1991:51). As distinct from the dramatic overthrow of the Tai absolute monarchy by the military in 1932, the Luang Prabang monarch under the French had already lost absolute authority and then become increasingly a symbolic figurehead, something which was formalised by the formation of a Lao national government in 1947. The king's ritual calendar had encompassed Vientiane after 1941 when the Luang Prabang sovereign's rule was extended south following the temporary loss of

(2). Within current nationalist discourse promoted in Laos these strategic concerns of the king are not taken into account and he is simply pilloried for wanting to invite the French back. That the king had his own game plan with the French is rarely acknowledged; for example, his demand (combined with a threat of abdication if the demand was not met) for an extension of the Luang Prabang monarchy's authority after the loss of Sayaboury Province to the Thai in 1941. Initially he sought suzerainty over the whole of Laos, but he settled for control over Vientiane and the whole of the north of Laos. (Royal ritual in Champassak in the south

Sayaboury to the Thai. Yet much of his ritual activity remained focused on Luang Prabang, and even as Lao king his ritual duties were largely confined to the northern parts of the country(3). All political parties proclaimed loyalty to the king, but the petty jealousies of a geographically and politically divided aristocracy, and the absence of political dictatorship, meant that there was no concerted state promotion of the monarch as there was in Thailand. Furthermore, during the 1950s the aged king was enfeebled by arthritis and other illness, and his son, Sisavang Vatthana, carried out most of his duties. The king's illness in turn, enfeebled the monarchy. By the time Sisavang Vatthana ascended the throne in November 1959 the nation was already deeply divided politically. The weak nation-wide education system contributed to disunity as well, for education systems are major instruments of modern nationalism. For example, the development of a modern, national education system in neighbouring Thailand has played a vital role in cultivating the cult of the king there. Charles Keyes (1991:116) writes: "More important than simply respect for the King is the idealization or even sacralization of kingship....King and Buddha are placed on equal planes for 'worship'...by the students and teachers. The educational program firmly establishes the monarchy as an important element in the villager's world view. The recognition of the particular Thai king and the idealization of the Thai kingship are the main elements which underlie the villager's sense of citizenship." In Laos much was made of o survey done in the late 1950s which showed that "only" 60 percent of Lao villagers could name their king (Le Bar & Suddard 1960:231; Fall 1969:128) (4), yet among, lowland Lao the king was much better known than any other political figure, especially in the villages. Lowland Lao knew of the palladium of the kingdom, the Prabang statue, and most could cite fragments of the legends of Lane Xang. Fall remarks, in the remote mountains among the "hilltribes" who make up a significant proportion of the population, one would not expect to find a strong awareness of the king. "The fact remains that the old King was, " writes Fall(ibid),"...a 'King's King' - courteous, wise, kind, and to the last endowed with a glimmer of humor and worldliness in his eyes that earned him the esteem of Laotians and foreigners alike". In August 1959 Crown Prince Sisavang Vatthana became regent, and in the political turbulence of the time "many Laotians associated the decline in health of their sovereign with the gradual disintegration of the kingdom" (Fall 1969:128-9). Sisavang Vong died two months later, and one commentator who attended his grand funeral in April 1961 commented:

The ashes of the old King were carried to their last resting place in a royal pagoda. The dignified little procession made its way through the narrow main street to the accompaniment

(3) Royal ritual in Champassak in the south remained centred on a descendant of the southern principality, Prince Boun Oum. In an annex to the agreement drawn up between the French and the Lao in August 1946 which recognised the unity of Laos under the Luang Prabang monarchy, Prince Boun Oum renounced all claims to sovereignty in the former southern kingdom, but retained his royal title. The Luang Prabang monarchy appears to have respected the ritual autonomy of the south, although the king or the crown prince regularly attended the Vat Phu and boat racing festivals in the south. (4) One gets the impression that these sources did not consult the original survey, but simply repeated press reporting at the time. The survey asked: "Can you tell me the names of the two most important leaders in Laos?' Among those responding at all, 'Don't knows' were given by more than half in Vientiane and in the capitals. Over three-fourths of the villages (villagers ?) also answered 'Don't know'. The king of Laos, Sisavang Vong, the most frequently named, was mentioned by about third of the respondents in Vientiane and in the capitals, and by a fifth of the villagers"(BSSR 1959:30). The prime minister at the time, Phoui Sananikone, was known by less than a third in the urban areas, but only 6 percent in the villages. After him the crown prince, Sisavang Vatthana, was better known than all other politicians, including Prince Souvanna Phouma (BSSR 1959:35). The interpretation of this survey is problematic for a number of reasons. First, commentators assumed that somehow ordinary Lao held a modern view of politics. Second, they tended to assume that people in modern industrial societies are well-informed politically. This is questionable. Opinion poll surveyors have often been shocked by the ignorance of the public about political affairs.

Of the thin sweet, Lao music, played on the traditional flutes, xylophones and drums. There was a gentle, sad finality about this last rite. It contrasted painfully with the military and political chaos in which the "ancien regime" of Laos seemed to be foundering. The King's funeral seemed to symbolize the probable demise of the old Buddhist monarchy itself. (Field 1965:130).

Arthur Dommen (1971:329) writes of King Sisavang Vatthana expressing deep pessimism about the future of Laos at this time as well, and is alleged to have said to Prince Sihanouk of Cambodia who was attending the funeral : "Alas, I am doomed to be the last King of Laos". Sisavang Vong is not forgotten. His large figure, located in a park outside Vat Si Muang which houses Vientiane's Iak muang, stares down at passers-by, and on several occasions I have noticed women kneeling before his statue, burning incense and praying to the old monarch (5). At the main temple in Luang Nam Tha in mid-995 I photographed a banner made of old 100-kip notes (which escaped the ceremonial burnings of the old kip notes in mid-1976), with proud profiles of the old king, hanging down from the ceiling of the temple to make merit for its donor. During research in the early 1980s on the attempted collectivization of the Lao peasantry, I sometimes came across faded photos of King Sisavang Vatthana hanging in battered frames in village houses. By this time photos of the old king were frowned upon and were being pushed aside by the ubiquitous photos of the main members of the politburo, in particular Kaysone, Souphanouvong and Faydang Lobliayao. I recall going into one house in 1983 where, above the window, hung portraits of the farmer and his wife when they were young; Souvanna Phouma, the former RLG prime minister, then still adviser to the new regime; and a photo of the Lao crown prince, Vong Savang. I asked what he was doing with photos of Souvanna Phouma and the former king's son still up in a prominent place. He smiled wryly and replied: " I keep them there to tell my children how bad the old regime was !". As has been remarked upon many times, the cities which housed monarchs in Southeast Asia represented sacred centres - centres of mystical and material power. The growing centralization of power focused on Bangkok over the late nineteenth and throughout the twentieth century, has further served to bolster the power of the Thai monarchy in all respects. By contrast, in Laos, the French established their administrative capital in Vientiane. There they built their offices, and also rebuilt traditional Lao monuments such as the That Luang and established conditions for the restoration and revival of Buddhist temples in the capital which had been left in ruins since 1828. Vientiane has remained the political capital of Laos to this day, but after 1947 the king did not move to Vientiane, although he was encouraged to by Lao Issara members (Deuve 1992:194). Luang Prabang simply became the royal capital of Laos. Thus royalty in Laos remained geographically aloof, or off-center, from the mundane world of real politics, and histories dealing with the period of the Royal Lao Government are punctuated by the decamping of the prime minister and his entourage to Luang Prabang to attend this or that festival and royal ritual, or of feuding politicians or ambassadors going to Luang Prabang for an audience with the king. Commentators on the bitter factional struggles that took place in Vientiane during the days of the RLG remark on the attempts by the king to play a neutral role. For example, Stevenson writes, "since 1959, Savang Vatthana, has played a careful balancing role, always

(5). This statue was donated by the Soviet Union in the early 1970s. A similar statue stands in the grounds of the old palace in Luang Prabang, described by two Swedish consultants as "a unique and quite impressive piece of 'socialism' (they seem to say this simply because it was made in the USSR)...one could be tempted to propose its removal, even if for no other good reason than for its sheer size and pompous monumentality" (Lind & Hagmuller 1991:51). The statue in fact is typical of its genre, and similar ones can be seen all over the world, including Sweden.

acting to preserve the royal position in the struggles between the various contending factions"(1973:13). Marek Thee confirms the impression that the king "did not wish to mix in the political game", and said "most of my Laotian contacts wanted the King to act independently, to play a balancing role" (Thee 1973:161). Recently released American archival material, writes Arthur Dommen, shows King Sisavang Vatthana "as a far more complex character than he has generally been portrayed" (1995:159), and strongly anti-communist. Nevertheless, he remained a conciliator and in fact delayed his coronation ceremony(6). Subsequently, LPRP propaganda has tried to insinuate that he was not really king because this rite had not taken place, when in fact it was delayed as a peacemaking gesture towards them, and it was the LPRP which in 1975 dissolved the coalition government formed in 1974 and made the coronation impossible.

In contemporary (private) discussions among some Lao about their recent history, when the role of the king comes up he is sometimes compared unfavourably with the Thai monarch. For example, Maha Canla Tanbuali, the senior Thammayut monk who defected to Thailand in 1976, said that while "the people did in fact love their King too,...they lacked the feeling of closeness to him, and the feeling of solidarity with him that the Thais have for their King" (1977:19).

But, when considering these remarks, one must be aware that Maha Canla was at one of the main royal temples in Bangkok, Wat Bowornives, and therefore was more likely to come in contact with the king. His retrospective remarks should also be compared to the observations of outsiders on the nature of Lao royalty. For example, Australian academic C.D. Rowley, then working for UNESCO, comments on travelling with the king's son and chao khoueng of Luang Prabang in the mid-1950s : "I was interested to see how easily M. Tay, a career official, took his place with the son of the King; and how the prince-governor consulted easily with his boatmen. One felt that in Laos the distance between the humble and the great is not really great" (Rowley 1960:169). Some Lao will opine that the Lao kings, unfortunately, were not as clever as the Thai king when it came to politics. Had they been, it is claimed, Laos would not become communist. And drawing on their observations of the Thai king as presented on Thai television today which shows him touring his kingdom and surveying various royally sponsored development projects, some people are likely to echo Maha Canla's sentiments and say the Lao king never did this and was not "seen". Of course, this is not true, and there is a great deal of evidence to show that the Lao king and his son the crown prince, also attempted to tour the kingdom, sponsoring religious celebrations and surveying development projects. But this was only recorded on newsreels which could be seen in cinemas, and not on the more powerful medium of television. In this

(6) François Gallieni reports in La Revue Française (Octobre 1967:23) that the coronation was planned for the end of 1968

way the much more visible (pre-TV) Lao king of yesteryear (7). But I recall a conversation with a taxi driver in Vientiane in 1995 who, wishing to offer me tourist commentary, informed me about without prompting that "we Lao once had a king like in Thailand, you know. And we respected him like the people in Thailand." These unfulfilled desires for a righteous monarch continue as part of the Lao social memory. King Sisavang Vatthana was forced to abdicate on 1 December 1975, a day before the declaration of the LPDR, and he and former RLG prime minister, Prince Souvanna Phouma, were appointed advisers to the new President Souphanouvong. "The abdication," writes Dommen, " deprived the majority of Laos's inhabitants of their country's soul, both spiritual and temporal"(1985:113). The abdication came as a shock to many Lao because the Pathet Lao had promised to retain the monarchy. Thus, Phoumi Vongvichit, was compelled in late December to respond to "rumours spread by the enemy that we had dismissed the King...Realising that the monarchy had blocked the progress of the country, the King abdicated and turned over power to the people. He is now Supreme Adviser to the President of the country. He is still in his palace, and still enjoying his daily life as before, and his monthly salary will be sent to him as usual. The only difference is that he is no longer called King" (SWB 31/12/75). After 1975 Lao royalty continued its off-center trajectory. Indeed in April 1876, the now ex-king Sisavang Vatthana was enjoined to vacate his palace in Luang Prabang. In a ceremony presided over by none other than Phoumi Vongvichit, the palace along with its relics, including the Prabang, were "donated" to the state as a museum and Sisavang Vatthana moved into Hong Xieng Thong, his private residence beside the royal Vat Xieng Thong. In March 1977, following pattikan activities in the north, with whom they were alleged to have had some association, the ex-king and his wife and two sons (Vong Savang , the crown prince, and Prince Sisavang) were arrested and sent to Houaphan where they apparently died of illness. Mystery still surrounds their arrest (8) and deaths, and the regime itself has never offered an official explanation, while the whereabouts of their remains is a closely guarded secret(9). As late as December 1996 I have overheard guides in the palace museum telling tourists that the king is still away "at seminar". When challenged about the truth of this they say the king's whereabouts is a "state secret". Prince Souvanna Phouma, on the other hand, continued to act as an adviser to the president until his death in January 1984, whereupon he was given a state funeral. Led by chanting Buddhist monks and his half brother, President Souphanouvong, his cremation took

(7) In Evans (1990a:113), however, I cite a rather idiosyncratic counter-memory of the king by a Lao co-operative head: "The television had shown the Thai king, who he remarked was a good leader, and his family out inspecting co-operatives (in Thailand). To which he added the observation that the old Lao king had been a good gardener, implying that he too would have approved of co-operatives." (8) The day after the arrest the governor of the province called a meeting of government functionaries to explain that the ex-king had been sent to Vieng Xay in Houaphan province. Three days later, Phoumi Vongvichit arrived to explain to these same officials that the ex-king would stay in Houaphan until he had been 're-educated". A tuk tuk driver in Vientiane who said he was in the Lao Revolutionary Youth movement in Luang Prabang at the time of the king's arrest claimed the following story was circulated by the party in Luang Prabang : On the day before the king was taken away a shaman suddenly appeared in the quarter near the palace. When police tried to capture him he would simply slip out of their hands. When they tried to stab him with a knife it would not cut him and when they tried to shoot him, bullets would not penetrate him. According to the story circulated, this man was a danger to the king and therefore the police persuaded the king to fly away with them in a helicopter. Perhaps some version of this story was in fact circulated in Luang Prabang. It expresses a certain paranoiac logic in as much as the new regime felt it was dealing with uncontrollable opposition forces, while the king was also under threat from forces beyond his control. The two ideas come together in the story. (9) During visit to France in December 1989 Kaysone finally confirmed that the king had died of malaria in 1984, but no other details were provided. Only in the proof-reading stage of this book did I read Christopher Kremmer's (1997) excellent account of his attempt to trace the final movements of the king.

Place at the That Luang pagoda, but his remains were taken to Luang Prabang where they were interred in a family stupa at Vat That which also contains the remains of the legendary Prince Phetsarath, his older brother.

Phetsarath was the son of the uncle and viceroy, ouparat (10), to King Sisavang Vong, and grew up with the king. He studied in France and briefly at Oxford, returning to Laos where he earned a reputation as an effective administrator. He was elevated to the position of ouparat in 1941. He played an important role in the Lao Issara (Free Laos) government which seized power in Vientiane in October 1945 after the Japanese surrender. Against the will of the king, they proclaimed their independence from France, leading them to depose the king briefly which left Phetsarath as head of state. This government was soon dispatched by returning French forces, and its members fled to Thailand, forming a "government in exile". Over the next few years, due to substantial changes in the relations between Laos and France which satisfied the aspirations of most of the Lao Issara members, the Lao Issara was dissolved in 1049 and its members returned to Vientiane, except Phetsarath and Souphanouvong (11). The latter went to work with the Viet Minh and participate in the formation of the Lao communist party, while Phetsarath remained in exile until 1957, when he returned and was reinstalled as ouparat. He died in late 1959. Because of his role in the Lao Issara, of which the LPRP claims to be the heir, Phetsarath remains a legitimate royal figure under the LPDR. In recent years a cult not unlike that surrounding Chulalongkorn has began to form around him and so one will often come across his photo in houses, shops or temples. For example, I asked the monks as Vat That Luang Dai in Vientiane why they had a picture of Phetsarath up on the wall in the sala instead of the old king; "Because he was on the revolutionary side. You can't use the old king." Significantly, permission was given by the government for the publication of Maha Sila Viravong's biography of Phetsarath (originally penned in 1958), and it appeared in print in August 1996. But Phetsarath is a popular figure not primarily because of his political role, although important legends have grown up around this, but because he is considered to have magical powers; he is saksit(12). This reputation partly arose from his deep interest in astrology, about which he published a book in Thai in the 1950s. Anthropologist Joel Halpern recounts how during an expedition with Phetsarath in Luang Prabang in 1958, villagers would approach Phetsarath to carry out purification rites. He also tells stories he heard about the prince :

One asserted that Prince Phetsarath had the power to change himself into a fish and could swim under water for long distances. It was said that bullets could not harm him. He was also reputed to have the ability to change his form, so that at a conference with the French at the time of the Free Lao Movement, he became angry with them, changed himself into a fly, and flew out the window...People from many parts of the Kingdom often write to him requesting his picture, and some of them place it in their rice fields to keep away malevolent spirits.(Prince Boun Oum is felt by some to have similar powers).(Halpern 1964:124)

On the other hand, Maha Sila's account (1996) of Phetsarath's life, interestingly, emphasises

(10) The ouparat, often translated as the "second king", played a key administrative role in the traditional political structure. (11) A proper analytic history of the Lao Issara, and Phetsarath's political career remains to be written. No doubt it will reveal a much more complex, and perhaps less heroic, view of the prince. Phetsarath's own account of his role in contained in a, "autobiography" that he published anonymously as "3349" in Thailand in the mid-1950s, and it was later translated into English.(See Phetsarath 1978.) (12) Saksit is usually translated as "holy", "sacred", or "powerful" in dictionaries, and it most often combines all these meanings.

how the prince was able to overcome local superstitions and fear of, for example, dangerous spirits inhabiting forests or lakes, through rational rather than ritual action. But ideas about the prince's magical powers are still widespread. His pictures are used for protection against malevolent phi (spirits), a protective amulet of him is now on sale, and in the current lottery mania in Vientiane it is said that you have a genuine picture of Phetsarath you can divine the lottery numbers. A tract I acquired from a holy man outside Vientiane contained a picture of Phetsarath, alongside those of a buddha and other sacred images, with protective holy words written in tham script surrounding his head like a halo. This same monk suggested that Sisavang Vong also had special powers, but not Sisavang Vatthana(13). When I asked a shopkeeper in Luang Prabang who kept a picture of Phetsarath on the wall whether he was more respected than the old king he replied: "Yes. Phetsarath was saksit. He could go for days without sleeping, walk in the rain without getting wet, and could fly up and sleep in the crown at the top of the forest". And there are other elaborations and variations. It is this religious or "priestly" role which keeps Phetsarath alive in the memory of Lao today. He was not a communist like his younger brother Souphanouvong, neither did the line up with anyone else under the RLG. He simply maintained his stature as a leader of the Lao Issara. This makes memory of him politically acceptable. This is most apparent in the realm of ritual. The New Year ceremony at Bassac (Basak) described so carefully by Archaimbault (1971) has been completely suppress. Prior to 1975, the New Year ceremony was centred on the figure of Boun Oum who would in the first days of New Year celebrations go in procession to the cardinal points marked by the vats in Champassak to expel (bok) evil influences from the muang (principality). It would culminate on the final day with a calling of the spirits of past rulers of Champassak by a moh tiam and in a baci ceremony at the main house of Boun Oum, where on this day the palladium of the principality, the pha gaew pheuk, would be brought out, and the local populace would file past the prince himself sprinkling him with water as a blessing. There are parallels in this ritual with the one conducted in Luang Prabang, which I describe in the chapter " Customising Tradition", but unlike the ritual in Luang Prabang, it has not been revived in recent years. Today, the bok ceremony is no longer practised, and all rituals which express the structure of the old muang have disappeared. New Year in Champassak has been atomised, and celebration, if any, occur only at the level of the respective baan and most commonly in individual households. The moh tiam ritual has been revived, and the spirits from across the city of Champassak are called, as are the spirits of past princes. But for the people at the ceremony I attended, these princes were non-specific, and people were content to simply say that many princes come (lay ong ma), though they were quite explicit that Boun Oum's spirit did not attend.

(13) This, of course, conforms to the traditional cosmology of kings. Kings who reign successfully to the end of their lives, by definition are phu mi boun, men of exceptional merit. King Sisavang Vatthana was overthrown, and therefore by definition did not have sufficient merit. Other tales underline this, such as one which claims King Sisavang Vong forbade his son from attending his funeral; and a related story which claims that during the dressing of King Sisavang Vong for his funeral, a role reserved for the son, Sisavang Vatthana could not lift his father in order to carry out the task, thus showing he was not a true child of the king. Only Sihanouk (the latter in fact flew to Luang Prabang for the funeral) could lift him, which shows that he was in fact a true child of the king. The same storyteller continued by saying that Sisavang Vatthana's father was in fact an Englishman, which you could tell from the size of his nose. A final further "fact" from this storyteller was that Sisavang Vatthana had never placed a roof over the statue of his father outside Vat Simuang, and this also showed that he was not a true child of the old king. This rather bizarre tale of legitimacy and racial purity is spun out of the cultural fabric which attempts to rationalise the rise and fall of kings. Many other stories are told which "explain" his fall and de-legitimise him, such as that he could not speak Lao properly, for example, and could only speak French. This false claim is happily bolstered by Pathet Lao propaganda.

The moh tiam does not go in parade to the main house of Boun Oum as in the past because this is not allowed. Older people in Champassak are quick to remember these grand parades, but younger people have no memory of them at all. Since 1996 at Boun Oum's former residence the palladium has been placed on the veranda on the first day of the New Year ceremony (sangkhan pai, the day of the passing of the old year) for the ritual splashing by the populace, while a traditional orchestra plays (14). This slight allusion to past practice is all that remains of the traditional ceremony. Three days later on the first day of the New Year (sangkhan khun) a baci is held in the main house in front of the ancestral shrine, overseen by two large photos of Chao Khamsouk and Chao Rasadani (Boun Oum's grandfather and father, respectively). This ceremony takes the guise of a household ceremony, and the government seems determined to keep it there. Yet any visitor to the south, in particular to Pakse, cannot avoid the presence of Boun Oum because his huge, unfinished palace, towers over the whole city. In the early 1990s this was taken over by a Thai company and converted into a sixty-room Champassak Palace Hotel(15). "Whose palace was it?" is, of course, the logical touristic question. Thus is the memory of Boun Oum, who died in exile in Paris in 1980, kept alive. The advertising brochure produced by the hotel contains a brief reference to the fact that it was Boun Oum's palace (and this must be the first neutral reference to him inside Laos in the past twenty years), but curiously this is only in Thai and not in English. It is thought that only the Thai are likely to be attracted by a brush with royalty?(16). It has been the numinous figures of Prince Phetsarath and Prince Souphanouvong who have maintained a high profile for Laos's royal past. Souphanouvong became a powerful symbolic figure "precisely because, like all dominant or focal symbols, he represented a coincidence of opposites, a semantic structure in tension between opposite poles of meaning" (Turner 1974:88-9). Almost always referred to in official pronouncement as either "comrade" or "president", in everyday speech he was commonly called "Prince Souphanouvong". Interestingly, this lapse was also registered in the title of a collection of essays about him published in 1990, where in both Lao and English he was referred to as "prince". The title in Lao is "Prince Souphanouvong": Revolutionary Leader"(17). Unexpectedly, Pasason (30/11/95) also referred to him as "prince" instead of "president". Foreign journalists and politicians regularly called him the "Red Prince". In the run-up to the communist take-over Souphanouvong was seen to represent in his person continuity with the kingdom's past, and the Pathet Lao's claim to want national reconciliation, which was further embodied in Souphanouvong because the neutralist prime minister, Souvanna Phouma, was his half brother. When he returned to Vientiane on 3 April 1974 to join the short-lived coalition government, journalists spoke of the "almost hypnotic spell

(14) Several members of this orchestra had been sent off to "reeducation" camps after 1975. After ten years away, several of the instruments had fallen into disrepair and had to be remade. They began playing again in 1988 as the revival of "tradition" began. (15) Folkloric speculation about why Boun Oum needed so many rooms claims that it was so that the palace could accommodate his many concubines and girlfriends. Thus the building continues to symbolize the sexual potency of traditional rulers. (16) Indeed, I'm not sure what to make of this difference in texts. After all, hotels in Luang Prabang directly pander to French and other foreigners' fascination with old royalty. For example, at one hotel, the Souvannaphoum, the former Luang Prabang residence of Prince Souvanna Phouma, one can stay in what used to be prince's bedroom for a higher price compared with other rooms in a newly- built wing. Currently, on the outskirts of Luang Prabang a Thai company is constructing a huge hotel around the former residence of Prince Phetsarath. (17) The English title is Autobiography of Prince Souphanouvong, published by the Committee for Social Sciences, Vientiane, 1990. However, the book is not autobiographical.

of Souphanouvong", and of a "new era" in Laos history:

Possessing a degree of vitality that was unusual in a Lao politician, he drew enthusiastic and demonstrative crowds wherever he went. He seemed at ease in any company, a veritable "people's prince whose rapport with the populace was reminiscent of Prince Sihanouk of Cambodia, though Souphanouvong was more reserved and he had a sense of mission. He had come to restore Laos' faith in itself. He was the hero of the Lao students movement. He had presence, if not charisma, and this rubbed off on the men who came down from Sam Neua with him. (FEER 1975:208)

He was a powerful symbolic figure, whatever his personal beliefs. Indeed, there is little evidence that Souphanouvong personally was anything other than a committed communist political activist (18). Because of his numinosity, however, many people wished to believe that somehow he was not deeply committed to the LPRP which he fronted for so successfully. Even after "the abolition of the outdated monarchy" (Kaysone's words), the aura of royalty clung to Souphanouvong and made him a symbolic enigma to the end. For this reason, on his death on 9 January 1995, one may have expected an overflow of nostalgia for the past(19). The state, however, maintained strict control over the funeral. Five days national mourning was declared for "one of its best loved leaders", and his body lay in state at the National Assembly until the final high Buddhist funeral ceremony on 15 January. The tears rolling down the cheeks of some monks, those who should have been most detached, perhaps bore silent witness to this final physical break with the royal past in the public sphere of Lao politics. As with Souvanna Phouma there had been some speculation about whether the funeral would be held in Luang Prabang, or whether his ashes would be returned there. But, one hundred days after the cremation, led by fifteen monks, Souphanouvong's family made merit for him along with President Nouhak and other party leaders, and his ashes were placed in a stupa at That Luang. To bury him in Luang Prabang would have reconfirmed that city's claim as a royal and ritual center(20). Souphanouvong, however, now rests at what is today firmly established as the national shrine, That Luang. While this may seem to be the final eclipsing of the Buddhist monarchy by secular politics based in Vientiane, the shrine where he rests is a Buddhist shrine built by a Lao king.

(18) He was a long-time associate of the Vietnamese communist leaders. Nevertheless, foreigners and some Lao like to insinuate that Souphanouvong's communist commitment can be attributed to the influence of his Vietnamese wife. The suggestion rests on an inference of "scheming Vietnamese", a sexist inference of "scheming wives", and also the inference that a "real Lao", and especially one who was raised as a prince, could not have chosen of his own free will to become a communist. There is no good evidence for these inferences which are supported primarily by popular prejudices. I have suggested elsewhere (Evans 1995:XIX) that the traditional system which allowed major and minor wives produced jealousy and disaffection and a search for alternative routes for advancement by those in a minor line, and that this may apply to Souphanouvong. (19)In fact, after 1975 it is not at all clear how popular Souphanouvong was. Many people associated with the RLG saw him as having betrayed their trust and his own royal heritage. Indeed, these days, one rarely sees photos of Souphanouvong displayed in offices, shops or houses. If anything, he is completely overshadowed by Phetsarath.

(20) Souvanna Phouma's ashes were taken to Luang Prabang and placed in a stupa at Vat That. This stupa also contains the remains of his older brother, Prince Phetsarath, and some assumed that Souphanouvong's ashes may have been destined for this stupa too. Vat That in Luang Prabang was historically connected with the "Vang Na", the front of the palace, compared with Vat That Luang in Luang Prabang, historically connected with the "Vang Louang", the central palace, and the remains of King Sisavang Vong rest there in a large stupa. Souvanna Phouma, despite his titular status under the LPDR, was part of the old regime, and not as symbolically important as his half brother, and therefore there was less political need to control the disposal of his remains.

Nothing, perhaps, registers the continued symbolic ambiguity of Souphanouvong's royal heritage better than the fact that no member of the Thai royal family attended his funeral, whereas HRH Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn, as representative of King Bhumibol Adulyadej, and HRH Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn, attended the funeral for Kaysone. While the attendance of royalty at Souphanouvong's funeral is more "logical" that at Kaysone's, it would have focused too much attention on his royal, rather than revolutionary, lineage. Yet, almost as substitutes for Laos's "disappeared" royalty, Thai royalty since 1990 has been playing an increasingly important, if subtle, role in Lao. They act as patrons of development projects, just as they do in Thailand, and as Lao see to obliquely recognise the parallel. Indeed, on walls in shops and businesses and in private homes throughout Laos, one will find calendars with pictures of Thai royalty occupying the same place that Lao royalty would have occupied in the past. In the showrooms of some retailers in Vientiane one can see proudly displayed the photo of an elite Lao family during their audience with the Thai king. Others who have met Princess Sirindhorn also proudly display photos of their encounter. Calendar pictures of the Thai king by himself or with his wife, and calendars with pictures of Princess Sirindhorn, or the crown prince of Thailand can all be found. While these are distributed much less widely than in Thailand, their mere presence is significant because of the symbolic space they occupy, and because similar pictures of the former Lao king, have been taboo. This taboo appears to apply especially to Sisavang Vatthana, and less strictly to Sisavang Vong. It was only after 1990 that people started to bring out of hiding old photos of the former kings, but much of this memorabilia had been destroyed after 1975, and is not reproduced yearly on calendars, for example, as with Thai royalty (21). Thus there is diminishing supply of such reminders of the Lao royal past. On the outskirts of Luang Prabang, in a Lue village which has historical connections of such memorabilia, combined now with the cult figure of Chulalongkorn. In his essay on the first visit to Laos by Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn (commonly known as Prathep), in March 1990, Charles Keyes (1993) investigates the way her visit registered, symbolically, Thai recognition of the independence of Laos, and of the revolution. This she did by visiting several key places and monuments in both Vientiane and in Luang Prabang. While in Luang Prabang the princess also met twice with the widow of the Lao crown prince, Princess Maneelai. Keyes learned that "when Princess Sirindhorn approach Princess Maneelai she saluted her by putting her hands together and bowing so that her head was lower than that of Princess Maneelai's. This indicated that Princess Sirindhorn acknowledged that Princess Maneelai was of high status". He continues: "I was told by a number of Lao...that the respect she showed Princess Maneelai helped to bring the Lao royal family back to popular attention in a positive way". Keyes was encouraged by the fact that when he visited Luang Prabang in 1993 he found a small hotel had been opened by Princess Maneelai and was called Villa de la Princesse. There is no doubt that the existence of this hotel brought the old royal family back into public view in a way not seen since the revolution. But it is interesting to also note the subtleties of this manoeuvre. The owners were careful not to use the Lao name for princess (chao ying, lasabudii), thereby invoking the officially abolished rachasap (royal language) but simply transliterated the French name into Lao ( ). Nevertheless, during 1994, pressure was brought to bear on the hotel by local authorities to change its name to Santi, for they were clearly disturbed by this resurfacing of Lao royalty (22). In 1996 the new name was

(21) In 1988 Lao refugees in America produced a calendar with a picture of Sisavang Vong on it, but naturally only a few copies found their way into Laos. (22) In Vientiane around the same time a guest house called Wang Sadet, "Princess's Palace", also had to change its name. The Champassak Palace Hotel transliterates "palace" into Lao ( ).But this use of "palet" may simply be the Thai use of English, as the Grand Palace in Bangkok is commonly called the "Gran Palet".

Displayed outside, but the old plaque still hung on the wall behind the reception desk, and the stationary still carried the old name. Indeed, taxi drivers and locals all continue to call it the Hong Haem Princet, and so the quiet tug-of-war between popular and official views continues(23). Perhaps it was the visit by Princess Sirindhorn which supplied the impetus for this move back into the public eye by Lao royalty, and the Lao authorities have acted to nip it in the bud. There has been no repeat meting between the Thai princess and Princess Maneelai since 1990. Prathep appears to act as the special envoy of Thai royalty to Laos. She has visited Laos every Year since 1990, travelling to different parts of the country to familiarise herself with it and to hand out largesse at schools and hospitals, and of course to be received enthusiastically by the various chao khoueng and their wives. She has given large donations to two of the oldest royal temples in Luang Prabang and elsewhere in Laos. She has, in a sense, become Lao's princess (24). The most important occasion, however, was the visit of the Thai king and queen to Laos on 8-9 April 1994 for the opening of the Lao-Thai Friendship Bridge. It was the first visit abroad by the Thai king in twenty-seven years, a significant fact in itself. But it was also significant because the Thai king had never visited Laos when it was a kingdom. Only when the Lao king was no longer present did he visit. Indeed, it is said that for as long as there was a king the Thai king could not enter the Lao kingdom. This parallels the story of the relationship between the Prabang and the Emerald Buddha, the palladiums respectively of the kingdoms of Laos and Thailand, in which it is said that they cannot coexist within the same space. Thus the Prabang which was taken to Thailand in the nineteenth century following the sacking of Vientiane was returned by King Mongkut in 1867 because it was considered a "rival" of the Emerald Buddha (Reynolds 1978). King Bhumibol and King Sisavang Vatthana did meet once, however, on a floating pavilion moored in the middle of the Mekong River off Nong Khai on the occasion of the inauguration of the Nam Ngum Dam on 16 December 1968(25). Photos at the same time show the much younger Thai king and the Lao king, both dressed in ceremonial military uniforms shaking hands. In April 1994 the Thai king once again stood in the middle of the Mekong, this time in a pavilion erected on the new bridge, and this time with the aged communist president, Nouhak Phoumsavan. That night after a reception at the Presidential Palace in Vientiane a Loa orchestra played songs composed by the Thai king. The next morning the king paid an official visit to the national shrine, That Luang, accompanied by President Nouhak, Prime Minister Khamtay, and a large entourage. The king and queen and the princess offered flowers, incense and candles as tribute to the Lord Buddha while monks chanted their blessing. They then made offerings to the monks and presented a contribution to the president of the Buddhist Association, Venerable Vichit Singalat for the maintenance of the stupa. It was pointed out in the Lao press that "the King showed keen interest in the rehabilitation of Buddhist monks and the civic and religious role activities of Buddhist monks in the country"(VT 8-14/4/94). After That Luang they visited an orphanage placed under the patronage of the princess during a visit in 1990, and again in

(23) It is perhaps worth noting that in advertising outside of Laos the hotel combines "Villa de la Princesse" and "Villa Santi" and invites tourists to come and stay in the old royal quarter of Luang Prabang, whereas inside Laos only the latter name is now used in advertising. (24) Rumours which circulated, particularly in Luang Prabang, have idly speculated about the possibility of a "dynastic marriage" between a Lao prince now living in exile in Paris, and Prathep. In fact, this is nothing more than rumour. But what is of theoretical interest to us here is the wishful and nostalgic element contained in the rumour. (25) Ngaosyvathn (1994:24) incorrectly states that this meeting occurred in 1972.

1992, and for which she had raised the equivalent of 342,000 baht and donated a further 285,000. While there, the king officially opened a building named after the princess, donated teaching aids and made a personal financial contribution. Later they visited an agricultural development and service center north of Vientiane established jointly by the king and the Lao government, which according to a speech by Lao foreign minister Somsavath Lengsavad, was established to commemorate the late President Kaysone Phomvihane and as a symbol of friendship between the two countries. In an audience with the king that afternoon Thai businessmen in Laos donated a further 2,5 million baht in support of this royally sponsored project, a conventional way for Thai business people to earn merit through association with the king. Finally, a baci, sponsored by the president and the prime minister and their wives was held for the royal couple and the princess at the Presidential Palace. In attendance were all the ministers, vice ministers, selected high officials and their wives. The seating arrangements only partially conformed to Thai protocol. The Lao president and prime minister and their wives sat on chairs at the same level as the Thai royal visitors underlining their equality, while before them seated on the floor around the pha khouan, were the Lao high officials and their wives, acknowledging their own ritual inferiority (VT 11/4/94). What is striking about this occasion is the ease with which the Lao officials and their wives conformed to royal protocol, and the obvious delight they took in moving within the charmed circle of the Thai king. One of the most important occasions in the ritual calendar of the Thai king is the kathin ceremony held at the end of the Buddhist lent. In October 1995 the Thai king extended his yearly sponsorship of the sangha to Laos. General Siri Thivaphanh from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Thailand, on behalf of the king, offered one set of monk requisites and donations of 510,000 baht to Vat That Luang Neua in Vientiane for the renovation the temple and the promotion of Buddhism. What was most interesting about this occasion was that joining in the merit-making were President Nouhak, Prime Minister Khamtay, and Foreign Minister Somsavath. The offerings were made again in 1996 and it was as if the Thai king had become a proxy for Lao royalty.

-----ooOoo-----

GLOSSARY ( concerning just this chapter )

There is still no standardised way of spelling Lao words in English. Over the years many variations have appeared. Thus, the spellings used here may differ slightly from variants used elsewhere, but the terms should still remain recognisable.

Baci soul-calling ceremony or blessing

chao khoueng provincial governor

kathin robes given to monks at the end of lent

moh cham / tiam spirit medium

ouparat second king

pattikan reactionary

pha khouan / phakuan central flower arrangement for a baci

phi spirit or ghost

saksit metaphysically powerful

sala meeting hall in the temple

sangha the organisation of the monkhood

sangkhan pai the day of the passing of the old year

sangkhan keun the first day of the year

that stupa

vat / wat temple

CONTENTS

Communism Remembered 1 Identity@Lao.net 5 National Day 15 The "Cult" of Kaysone 24 That Luang: "Symbol of the Lao Nation" 49 Mediums and Ritual Memory 71 Bodies and Language 83 Recalling Royalty 89 Statues and Museums 114 Customising Tradition 129 Minorities in State Ritual 141 Rote Memories: Schools of the Revolution 153 Mandala Memories 168 Lao Souvenirs 185 Glossary 193 References 196 Index 208

For any further information please contact Dr. Grant EVANS : E-Mail :hrnsgre@hkucc.hku.hk

----------oooOooo---------- |